A Mistery of Curriers

The term ‘mistery’ has two meanings. In medieval London, crafts or trades were often called ministeria (Latin), mestiers (French) or misteries (English). Between 1100 and 1350, London’s population grew and its economy became more specialised and complex, so the mayor and aldermen began to delegate responsibility for supervising the city’s crafts to institutions which we now commonly call ‘trade guilds’. These guilds were associations of freemen who exercised a certain craft, and because these guilds were synonymous with their crafts, by a simple elision they were also called ministeria, mestiers or misteries by contemporaries.

When the mayor and aldermen recognised and authorised these bodies, they handed considerable power (in theory at least) to what was usually a self-appointed group within a craft to regulate labour and production within their craft. It is easy to understand why this happened. Misteries provided the urban authorities with a cheap means of supervision and they were a useful medium through which fines and amercements might be levied.

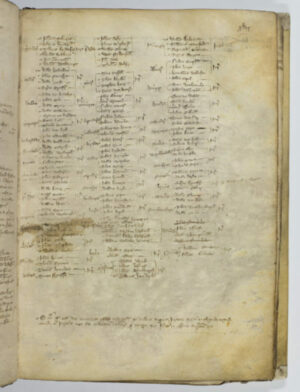

The curreours appear on a list of ‘divers misteries’ of London, which was drawn up in 1364, to record a total payment of over £450 to the city’s chamberlain to be forwarded to the king as a loan. On this occasion, it is unclear how we should interpret ‘mistery’. It might refer to a guild of curriers, it might equally denote a collection of individual curriers from within the trade.

In 1376, however, Richard Serne and Thomas Willingham were elected to London’s Common Council to represent the mistery of curreours, and by that time the curriers must have been organised into an institutional body of some sort.