Fraternity of Yeoman Curriers Established

In 1367-8, Richard Levered, John Herd, Robert Sharp ‘and others which now ben ded’ founded a fraternity ‘of the yomanrie of curreiours’. This is the oldest known fraternity of curriers in London. Fraternities provided a vehicle through which the men and women of late medieval London could come together to celebrate and express their devotion to a parish church, to the cult of a certain saint, to a particular feast day, or to a religious festival, for example Corpus Christi. Usually, their members worshipped and dined collectively, they came to the funerals of members, and they observed masses and obits for the souls of deceased brothers and sisters. They were especially popular with the poorer members of medieval society, for whom, in Caroline Barron’s words, they functioned as something of a ‘communal chantry’.

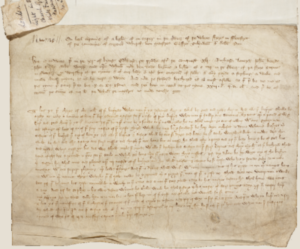

In 1388-9, the Curriers' fraternity’s representatives came into Chancery to answer questions about their organisation, and their answers survive in a return now kept at the Bodleian Library, Oxford. At that enquiry, the members were clear that their organisation was a yeoman association, which meant that its brothers and sisters were junior members of the contemporary craft. This may explain its apparent poverty (it had only 23s 2½d. in chattels and £4 in debts, the latter of which the masters, at that time Geoffrey Tollington and Robert Store, ‘ne mow nouyht gete’).

The fraternity was also based outside the city walls some distance to the south-west of the three parishes of St Giles Cripplegate, St Alphege London Wall, and St Stephen Coleman Street, where citizen curriers were most commonly found. Together, this evidence probably indicates that this fraternity represented a particular group of low-ranking and perhaps even non-citizen curriers who developed a distinct set of neighbourly rules in line with their specific interests.

The members of this fraternity also promised not only to uphold particular pious obligations, but also to abide by certain trade regulations. Written in English, it is one of only two or three such documents drawn up in medieval London known to have survived.